Jewish Ideas... a different look!

Today's conversations and presentations, so far, have made me think a lot about the power of ideas and how my Jewish identity and my experience as an intellectual shape who I think and interact.

We began the day in a conversation with an Israeli rabbi. He likened the questions we asked him to hazing...but he was good-natured and more open to differing views than I expected.

Rabbi Cohen presented the beginnings of Judaism in a way that's different from my understanding, but I like it, because for the first time, it made me feel connected with Abraham. Let me share it:

In the early days, he said, might makes right. The big power sources needed to be prayed to; that was dogma. The sun, the rain, the earth...all were divine by their size and importance. People worshipped these divinities and more.

Here's where it stepped out of my experience of biblical tales: Abraham, according to his story, didn't take dogma as truth. He questioned it. Instead of seeing the sun as all powerful, he realized that it isn't visible when the night comes. Instead of seeing rain as all powerful, he realized that it must succumb to the sun. And instead of seeing the earth as all-powerful, he realized it could be flooded.

In this view, Abraham was an intellectual, a thinker, a questioner. But he didn't just criticize the existing status quo of how his peers viewed the world. Instead, he kept thinking. He sought an entity that was above the sun and the rain and the earth, something that helped connect everything and everyone. And this, in Rabbi Cohen's story, is how he found God.

In my modern life, I've always seen a gap between intellectualism and religion. (I say this humbly and lovingly to all believers.) This view was different; it showed Judaism as awakening immediately out of intellectualism.

This suddenly made sense because our texts are years and years of dialogues between rabbis trying to make sense of the oral tradition and write them down for the future. This suddenly made sense because the iconic image I have of Yeshiva boys is a group sitting in a library disputing each word of the Torah. This struck me because we are known for answering questions with questions and for allowing (ay, encouraging) research on the day of rest.

Another eye-opener for me was Rabbi Cohen's retelling of Moses's journey, the forty years before arrival in Israel. In his version, before entering the land of Israel, the Jews needed to get rid of the slave mentality. They needed to learn to take responsibility for their actions, and not be ones who have actions dictated to them. Forty years was enough for a generation to be born and a generation to die, and for freedom to be put into the mindset of a culture. Plus, the addition of the Torah and a covenant now, with the Nation of Israel (not just Abraham, or a small family), included the understanding of an omnipotent, infallible, omniscient deity. This meant that any mistakes were not God's but humanity's. Responsibility became part of the mindset of a culture.

Now, I don't believe in omnipotence and all that, but this mix of intellectualism and responsibility means creating a society that thinks about how to make a better society. This is something I can hold onto.

One last tidbit from Rabbi Cohen. He spoke about the difference between Jewish Kings and the absolute monarchies of Europe. It made me chuckle to hear him call the decision of Israel to have kings as an act of Chutzpah. After all, if you have an all-knowing God, why do you need a human leader? However, he explained the importance of this addition to our culture by saying that it was important for the Jews of Ancient Israel to be able to take part in the rest of the world.

Having a king, then, was something practical. The king was not above people. There was a democracy and the law applied to everyone without exception. To keep the Jewish kings humble and aware of this, it was crucial that they carried a scroll with them at all times. This was to remind him that "you're a schmenkel like the rest of us" (a direct quote but modern understanding from this rabbi.)

Yes, I keep chuckling. Right now, we have a president who Tweets at all hours of the night. King Solomon, though, carried a Torah scroll with him even when he had to "do his business". A little different, huh?

So, after looking at the biblical roots of Questioning, Responsibility and Democracy, I realize how much this all is part of my own personal intellectualism. Earlier this year, I was told that I lacked integrity for not following directions. I'm not perfect and I'm sad that I give off wrong impressions. But I am an intellectual who is always questioning how to make things better, doing my best to make them better, and seeing us all as equal cogs in the human goal of world improvement. Maybe I'm delusional? But it felt good to see my life in this context.

We began the day in a conversation with an Israeli rabbi. He likened the questions we asked him to hazing...but he was good-natured and more open to differing views than I expected.

Rabbi Cohen presented the beginnings of Judaism in a way that's different from my understanding, but I like it, because for the first time, it made me feel connected with Abraham. Let me share it:

In the early days, he said, might makes right. The big power sources needed to be prayed to; that was dogma. The sun, the rain, the earth...all were divine by their size and importance. People worshipped these divinities and more.

Here's where it stepped out of my experience of biblical tales: Abraham, according to his story, didn't take dogma as truth. He questioned it. Instead of seeing the sun as all powerful, he realized that it isn't visible when the night comes. Instead of seeing rain as all powerful, he realized that it must succumb to the sun. And instead of seeing the earth as all-powerful, he realized it could be flooded.

In this view, Abraham was an intellectual, a thinker, a questioner. But he didn't just criticize the existing status quo of how his peers viewed the world. Instead, he kept thinking. He sought an entity that was above the sun and the rain and the earth, something that helped connect everything and everyone. And this, in Rabbi Cohen's story, is how he found God.

In my modern life, I've always seen a gap between intellectualism and religion. (I say this humbly and lovingly to all believers.) This view was different; it showed Judaism as awakening immediately out of intellectualism.

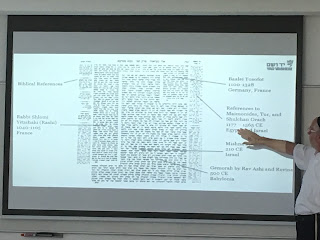

This suddenly made sense because our texts are years and years of dialogues between rabbis trying to make sense of the oral tradition and write them down for the future. This suddenly made sense because the iconic image I have of Yeshiva boys is a group sitting in a library disputing each word of the Torah. This struck me because we are known for answering questions with questions and for allowing (ay, encouraging) research on the day of rest.

Another eye-opener for me was Rabbi Cohen's retelling of Moses's journey, the forty years before arrival in Israel. In his version, before entering the land of Israel, the Jews needed to get rid of the slave mentality. They needed to learn to take responsibility for their actions, and not be ones who have actions dictated to them. Forty years was enough for a generation to be born and a generation to die, and for freedom to be put into the mindset of a culture. Plus, the addition of the Torah and a covenant now, with the Nation of Israel (not just Abraham, or a small family), included the understanding of an omnipotent, infallible, omniscient deity. This meant that any mistakes were not God's but humanity's. Responsibility became part of the mindset of a culture.

Now, I don't believe in omnipotence and all that, but this mix of intellectualism and responsibility means creating a society that thinks about how to make a better society. This is something I can hold onto.

One last tidbit from Rabbi Cohen. He spoke about the difference between Jewish Kings and the absolute monarchies of Europe. It made me chuckle to hear him call the decision of Israel to have kings as an act of Chutzpah. After all, if you have an all-knowing God, why do you need a human leader? However, he explained the importance of this addition to our culture by saying that it was important for the Jews of Ancient Israel to be able to take part in the rest of the world.

Having a king, then, was something practical. The king was not above people. There was a democracy and the law applied to everyone without exception. To keep the Jewish kings humble and aware of this, it was crucial that they carried a scroll with them at all times. This was to remind him that "you're a schmenkel like the rest of us" (a direct quote but modern understanding from this rabbi.)

Yes, I keep chuckling. Right now, we have a president who Tweets at all hours of the night. King Solomon, though, carried a Torah scroll with him even when he had to "do his business". A little different, huh?

So, after looking at the biblical roots of Questioning, Responsibility and Democracy, I realize how much this all is part of my own personal intellectualism. Earlier this year, I was told that I lacked integrity for not following directions. I'm not perfect and I'm sad that I give off wrong impressions. But I am an intellectual who is always questioning how to make things better, doing my best to make them better, and seeing us all as equal cogs in the human goal of world improvement. Maybe I'm delusional? But it felt good to see my life in this context.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thanks for your response!